The story of an older teenage boy’s, Taheim, first sexual experiences with the alluring Rasheed tells an all too familiar story of what happens to young men in the Black LGBTQ+ community. The short story “Lessons We Haven’t Learned Yet” from the book The Blue Street Stories is a cautionary tale about sexual health prevention and being young. In this blog, I discuss what the climate was like for Black LGBTQ+ men in the 90s and STDs.

Then in the 1990s, sexually transmitted infections took over the world and reached many communities. But for the Black LGBTQ+ communities, the question and challenge of race, sexuality and health was a different beast. STDs were highly stigmatizing and discriminatory, and deeply culturally embedded in these groups. In the history of STDs within these groups, we can learn about the persistence of health inequalities and the resilience shaped by intersectionality through race and sexual orientation.

In the 1990s, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) dominated Black LGBTQ+ communities. The diseases such as HIV/AIDS and syphilis affected these populations at a disproportionate rate, causing more morbidity and death. Health care resources were restricted because of socioeconomic inequalities, which made matters worse. There were lots of people in these groups who couldn’t afford the testing and treatment services, and many didn’t have them easy or cheap. Thus, untreated and undiagnosed STDs spread and created huge health problems.

The Black LGBTQ+ communities of the 90s faced a lot of stigma and discrimination on the one hand because of sexual orientation and race, and on the other side because of their health risks if they contracted an STD. The world took STDs for granted as the product of moral decay, and everyone a victim of its own fault. Within their communities, there were also those rejected for cultural discrimination against homosexuality and for misunderstanding sexual wellbeing. It wasn’t only this stigma that kept sexual health off the table – it also discouraged people from going for the care and support they needed.

It was culture that was determining attitudes and interventions for STD prevention and management among Black LGBTQ+ communities. The past distrust of medicine stood in the way because of immoral medical experiments like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. What’s more, male cultural attitudes toward men, anonymity and sexual behaviors influenced people’s attitude to preventive care and open sexual talk. It was against these constraints that grassroots communities formed – working towards culturally sensitive health education and peer-led programs – to provide inclusive, reliable health resources.

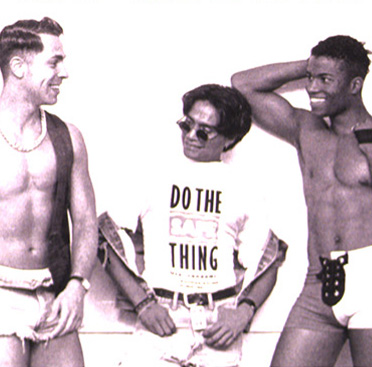

The 90s saw more and more activism around the effects of STDs on Black LGBTQ+ people. AIDS had hit its tipping point, and the inequality faced by those at the intersection of race and sexuality was underscoring. Community organizations advocated and educated, calling for more research and attention to communities. But for all this progress, many remained combative of structural inequality in healthcare provision and public health interventions. In black LGBTQ+ spaces, the 90s were the year that sexual health activism had a new emphasis on cohesion and visibility.

The intersectionality of race, sexual orientation and STDs among Black people is important to know how they face the compounded challenges. Black LGBTQ+ people are multi-identities that influence healthcare and social acceptance and are disproportionately isolated and discriminated against within and outside their racial and social communities. Understanding these cross-pollinated identities is essential for designing healthy interventions and policies that are adapted to these populations. Such an intersectional approach can help to break down walls and create spaces in which complete sexual health care is available and fair.

When we look at the health outcomes of sexually transmitted diseases for Black LGBTQ+ people, we see how a complex array social, cultural and historical dynamics play out. The reality of lived experience, with its racial and sexual identity, continues to matter as groups struggle for more health equity and representation. To combat the impact of STDs into the long term, ongoing campaigning, multisectoral public health interventions and community tenacity are needed to fight stigma and increase access to care. By knowing and appreciating these antecedents and continuities, there is the possibility to create a future of power and health justice for Black LGBTQ+ people.