As I republished my book, “The Blue Street Stories,” I will be posting some topics based on the themes of the book throughout the book’s launch. In the story “Is It Worth It,” Kareem finds out, after having lived a promiscuous lifestyle, that he has HIV. The story takes place in 1990s Philadelphia. I want to shift our attention on a glimpse of what it was like to have HIV as a Black gay man in the 1990s.

The 1990s – a tumultuous decade in the United States – saw a massive shift in the country’s socio-political landscape, as well as the emergence of what would become national health epidemics that targeted marginalized people. One of the groups most profoundly affected by this era were black gay men, who experienced the HIV/AIDS crisis in ways that were as unique as they were intersectional. The specificity of their vulnerabilities and responses can be understood only by looking at the history of race, sexuality and disease stigma that brought them together.

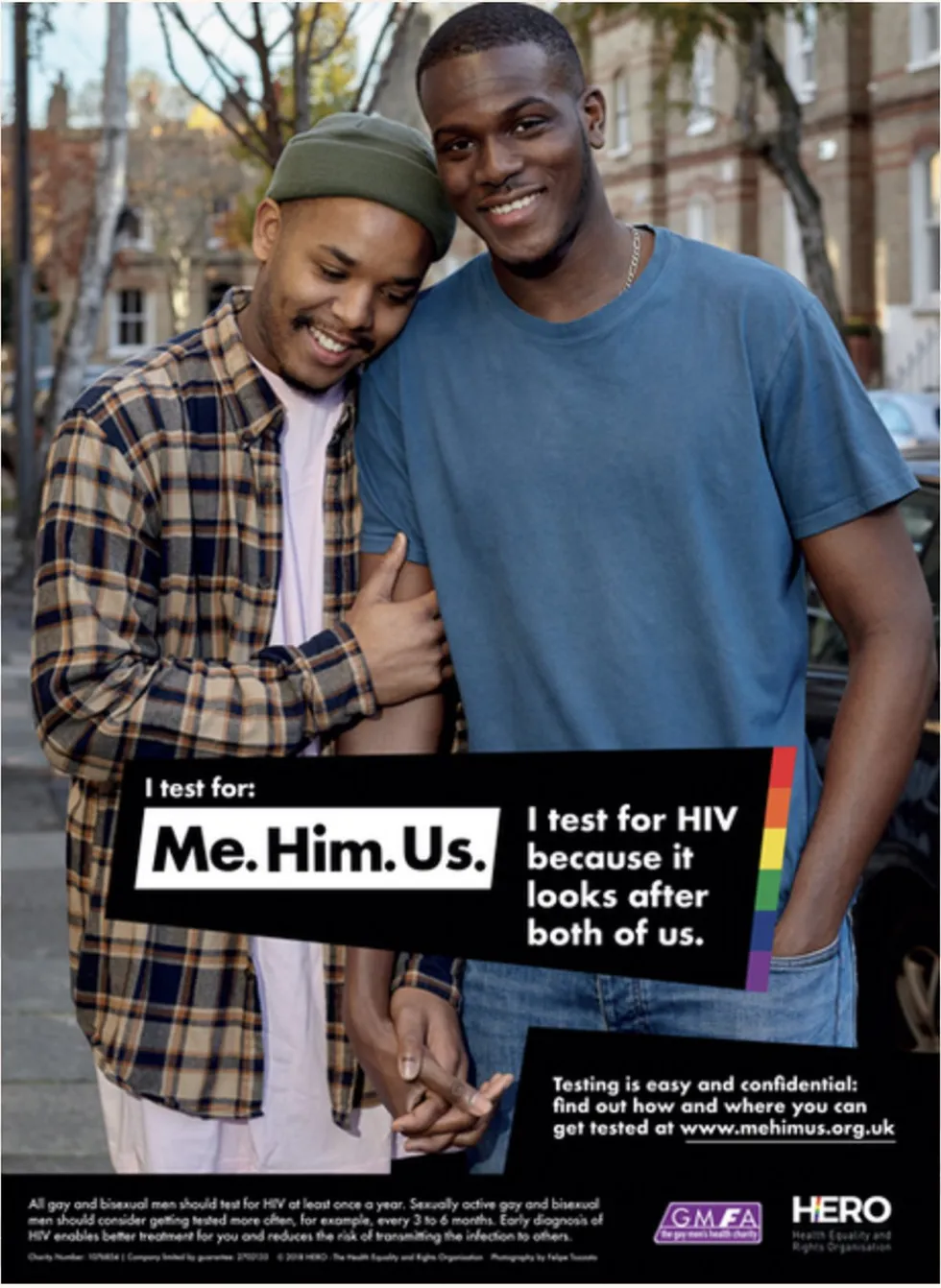

Through its disproportionate impact on African American gay men during the 1990s HIV/AIDS epidemic – where individuals faced compounding health and social disparities, including poor access to healthcare, intense stigma, and institutional indifference – disproportionately high rates of infection emerged. With such divisive effects, targeted public health initiatives were left wanting and black gay men, although being highly affected, were statistically underrepresented, and often omitted from public health prevention campaigns.

Black gay men also exhibited extraordinary resilience when trying to overcome the ravages of HIV/AIDS, race, class, economic insecurity and social isolation. Despite facing discrimination in a mostly culturally hostile healthcare system, too many black gay men had no financial security and too often existed on the periphery, isolated from much of mainstream support. And misinformation and fear created the need for much of the same.

People’s lives were made harder by the interaction of race and sexuality: they were trapped between two worlds. Black men were taught that being gay was unacceptable by both blacks and whites, and were therefore stigmatized at home and rejected elsewhere. Their struggles were impeded by the fact that racism in the white gay community and homophobia in the black community comprised their twin fields of pain; their identities showed that changing the epidemic with ‘standard’ intervention and support would require ‘special’ approaches, what we call intersectional approaches.

African American gay men’s art and culture, as a form of resistance and a means to mourn and heal, played an important role in the fight against the spread of HIV/AIDS and those who targeted its sufferers. As black gay men continued to die, the arts became a way for them to articulate their losses, strengthen their bonds of community, and educate the public, both gay and straight, about their plight. Literature, theatre, music, and even the visual arts allowed ‘research by action’ as people created protest songs, AIDS-themed theatre, self-healing memoirs, and even activist artwork.

As African American gay men with HIV/AIDS, they endured stigmatization and discrimination at every turn. AIDS had been further complicated by the fact that many of them already faced discrimination due to their blackness, and discrimination due to their gayness. This combination of stigma led to isolation: if most people ostracize you not just for being a homosexual, but for being black and a homosexual, there was no one to whom you could reveal your status, and no one to provide emotional support. In this way, stigma cemented the barriers to treatment, and to being accepted, isolating all affected from those who might otherwise be their allies.

In the face of these obstacles, as they forged new communities, gay black men were able to tell one another stories of resilience and resourced survival. They formed organizations and built communities of care and mutual aid, and shared stories of surviving and thriving in the face of adversity. This resilience – the margin of space they made for themselves and one another – was not just a source of individual vitality and power, but also a resource that black gay and lesbian people have mobilized as part of larger movements for equality and justice.

Historians of medicine have something to teach us about the wages of that neglect. Case in point: a history of African American gay men in the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1990s. While limited options left them vulnerable, Black gay men also built upon an existing legacy of survival and creativity. Their coping strategies teach us not only something about the power of community in fighting back against epidemics, but also the enduring potential of their example to inform present-day struggles against health disparities and the pursuit of racial equity.